June 2017

Patient is a 41 year old Caucasian female who presented with the Chief complaint of sudden pain on the left side of her face and dentition for the past 2 days. Her medical history is unremarkable with the only medication she is currently taking is Ibuprofen for the control of her sudden onset of pain. The patient was seen by her dentist and referred for evaluation of tooth #19 due to radiographic apical pathology.

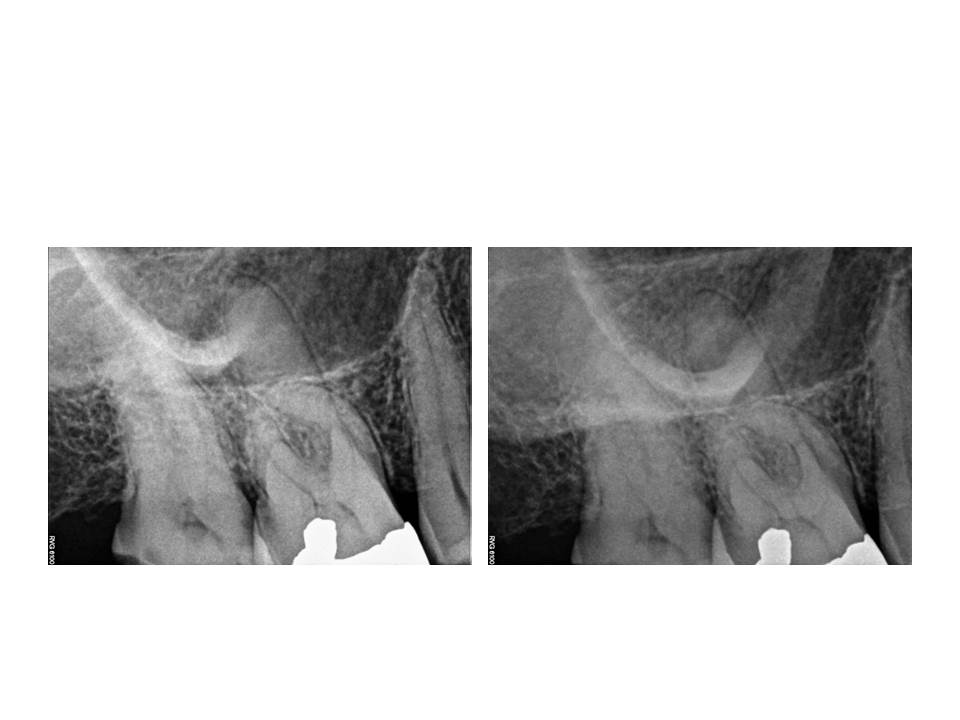

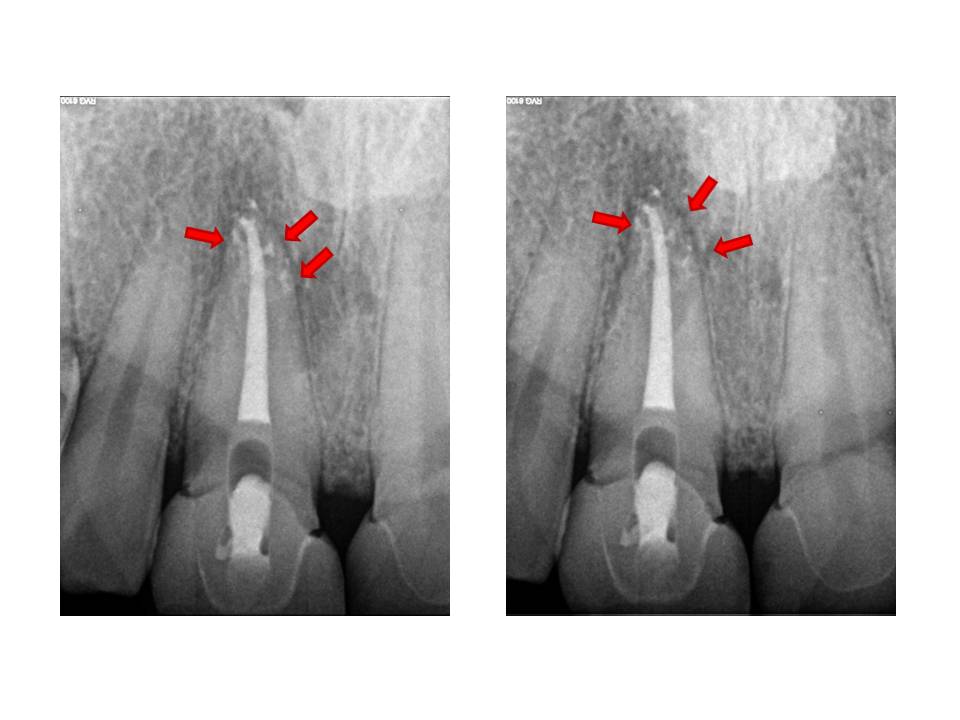

Clinically, tooth #19 has an MOD composite restoration with good margins, normal (similar to adjacent teeth) response to cold, negative percussion tenderness, slight palpation tenderness and very mild cortical plate expansion near the distal root end, normal periodontal probing depths, no mobility noted. Radiographs reveal conservative composite restoration present, a circular RL lesion (12 x 12 mm) associated with the distal root end. The outer 2-3 mm circumference of the lesion appears more radiodense while the center appears more lucent and has an irregular trabecular pattern.

External palpation of the left Masseter and Temporalis muscles produces some mild discomfort. From the clinical and radiographic exam, I will aske the question as to whether this is a LEO(Lesion of Endodontic Origin) or non–LEO?

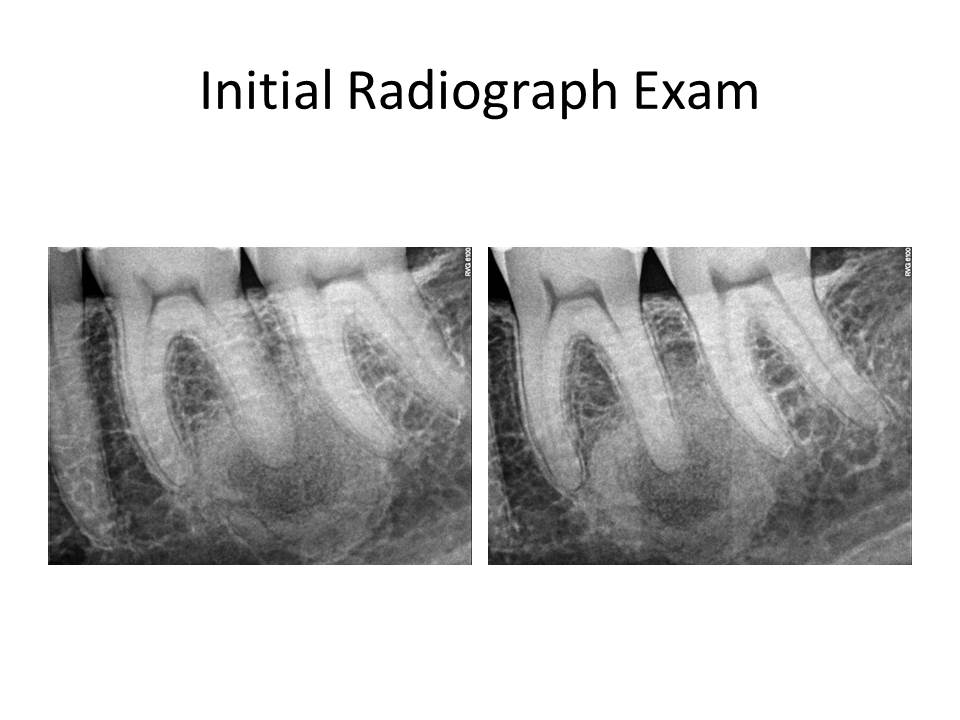

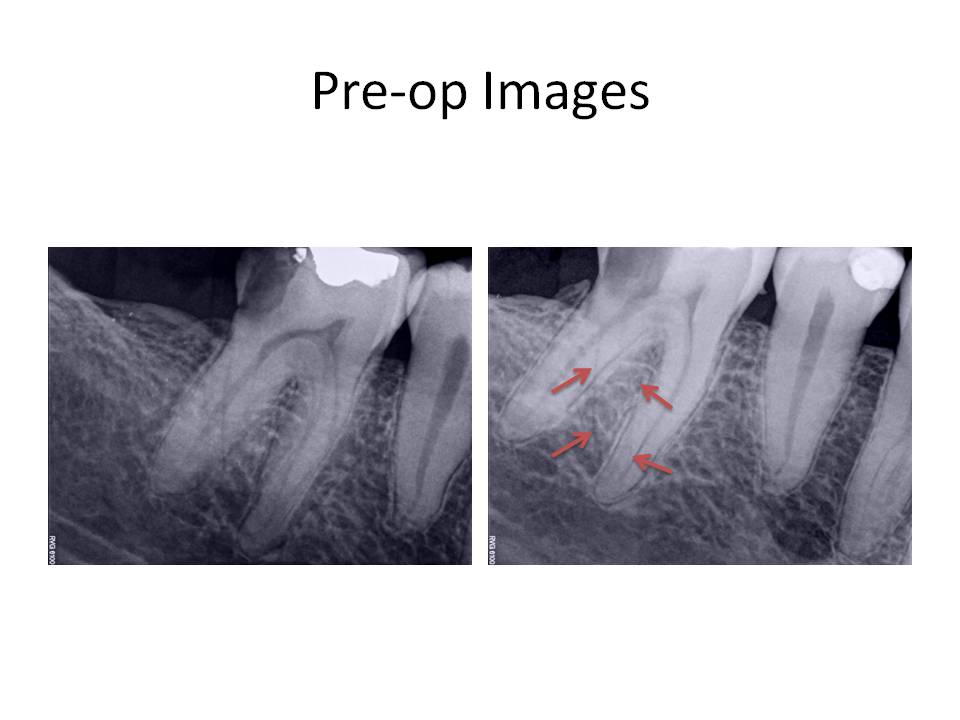

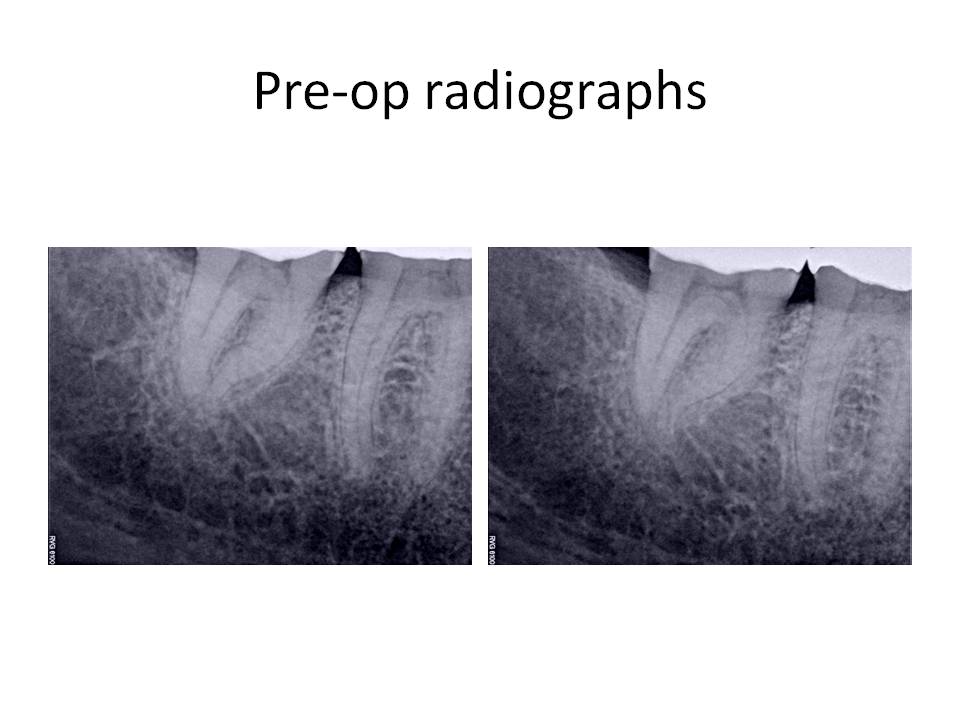

I present the radiographs for this case.

Since the tooth responded similarly to cold as the adjacent teeth and the restorative treatment was conservative, I initially did not think this was an endodontic issue. The pain the patient was reporting as sudden onset was actually related to nocturnal bruxism and stress as she was getting married in a few days. So, I have ruled out root canal treatment. What is the differential diagnosis? What are the potential treatment options for this case, if any?

My differential diagnosis included the following:

1. Ossifying Fibroma (early stage)

2. Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia

3. Simple bone cyst

4. Ameloblastoma

5. Keratocystic odontogenic tumor

The diagnosis is #2. Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia. Review of the patient’s pano did not reveal any other locale for additional pathosis. If so, this would be a case of Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia. Treatment is observation, unless the lesion becomes large enough to cause discomfort. In which case, enucleation of the lesion would be indicated. These lesions become problematic when they become large and communicate with the oral cavity. Also, hypovascularization can occur and these lesions can be prone to necrosis with minimal provocation. At this time, annual radiographic examination is the only treatment recommended.

Thank you for the opportunity to serve your practice and patient’s needs!

April 2016

January 2016

Case of the month Feb 2014

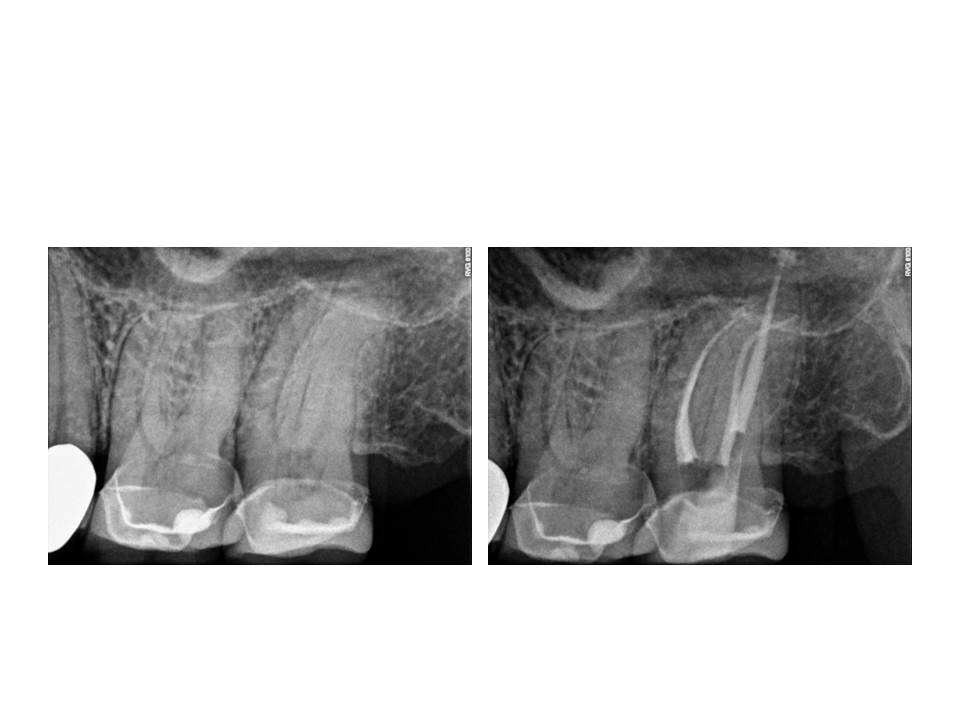

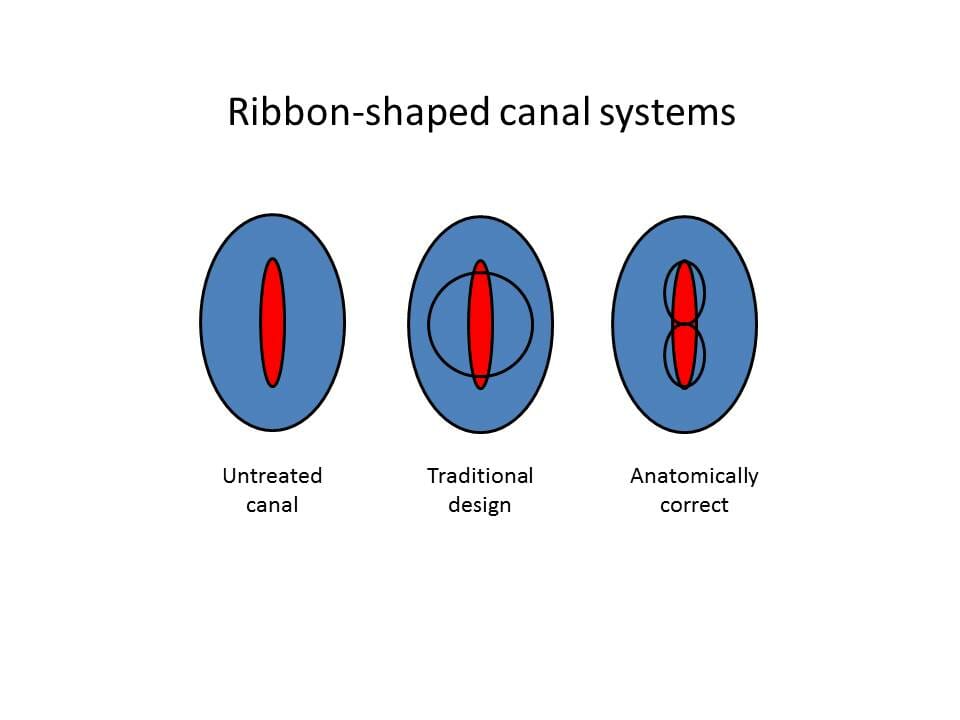

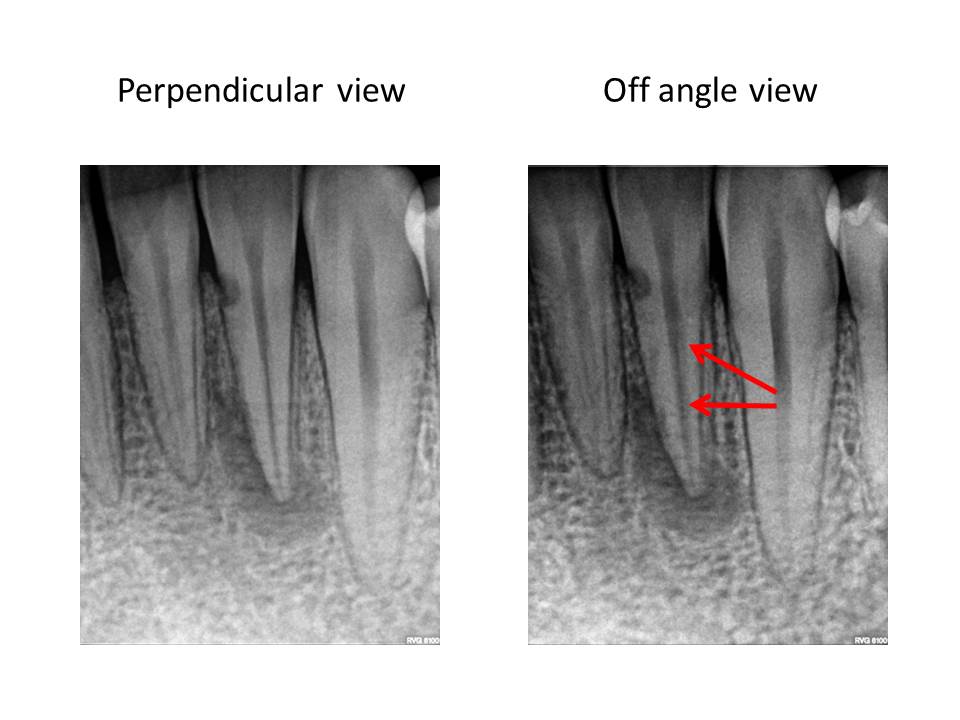

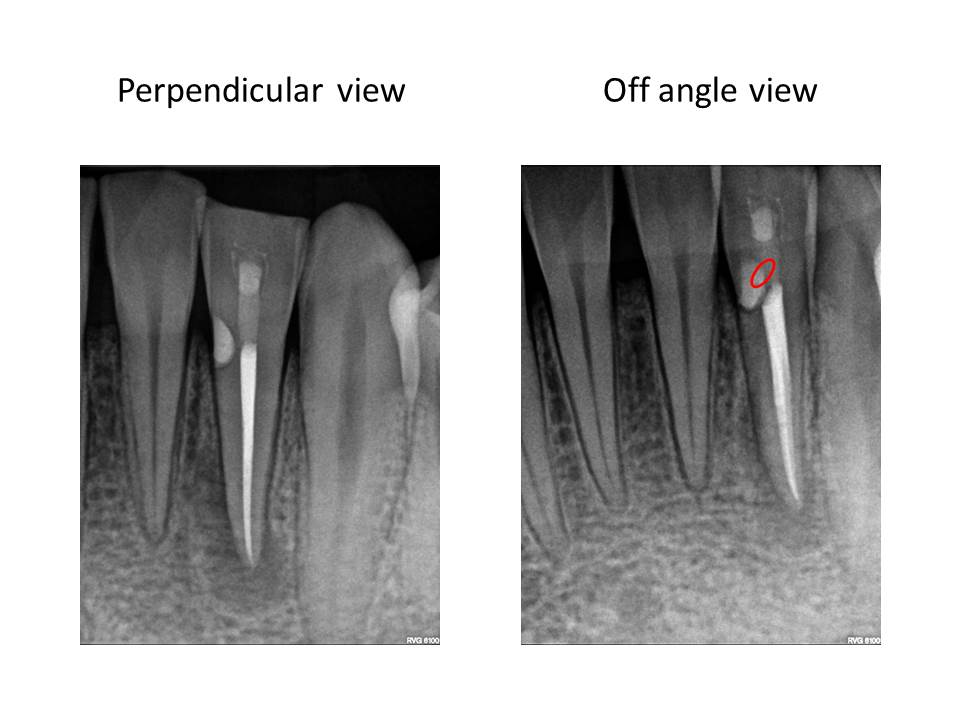

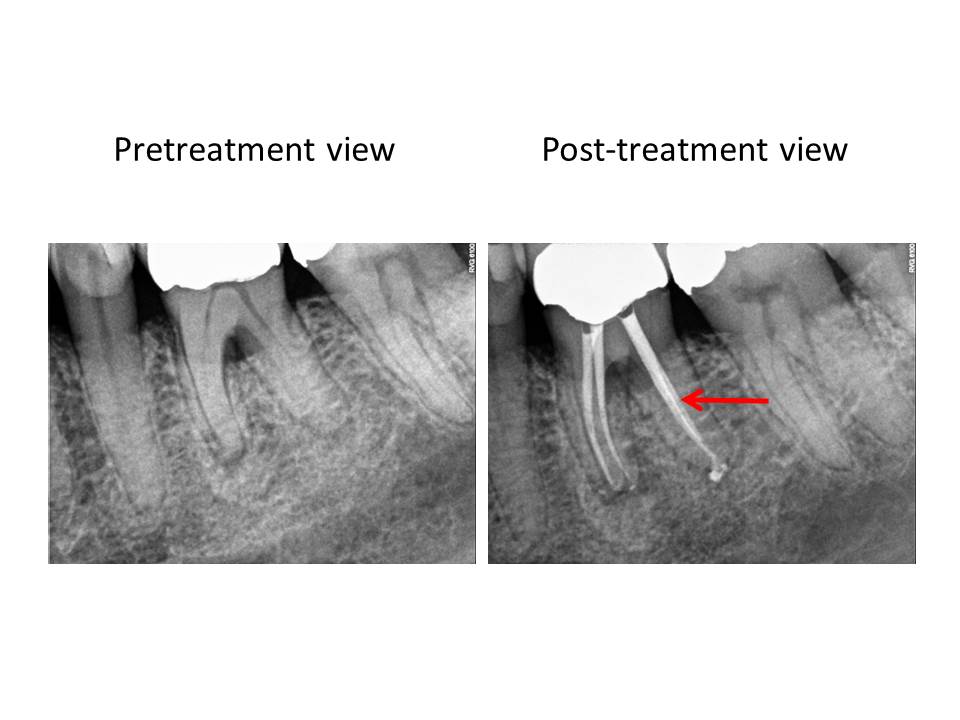

Therefore, I propose modifying the preparation to address the periphery first. This will result in a more conservative preparation. It will also better facilitate the cleaning and shaping the lateral extents of the canal system where typically a fair amount of debris is accumulated during the instrumentation process. This is an example of a mandibular incisor in which 2 canals were present.

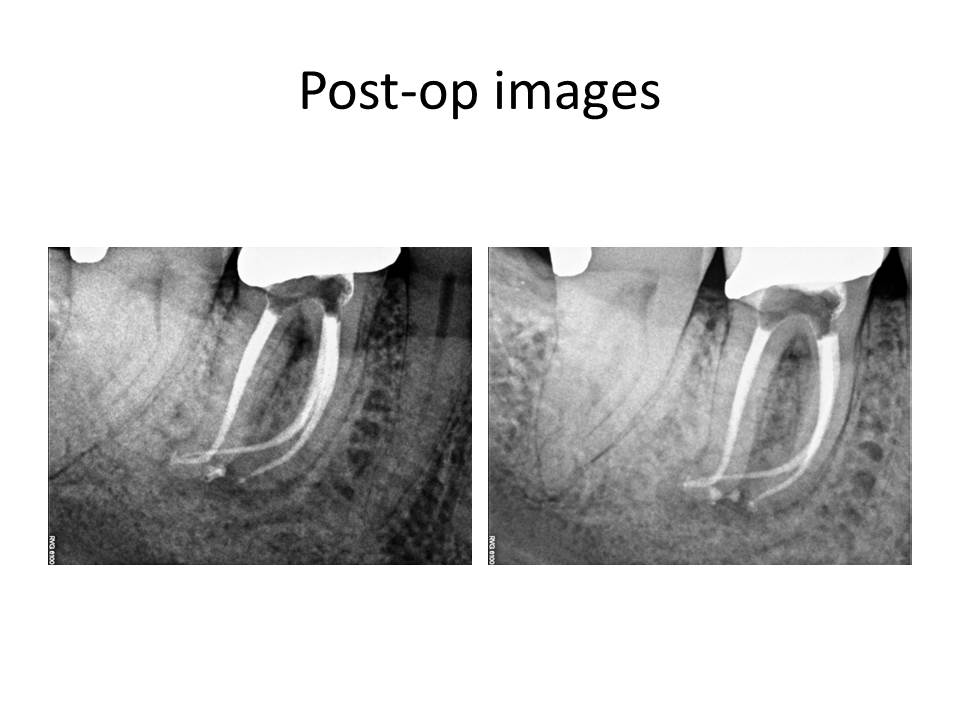

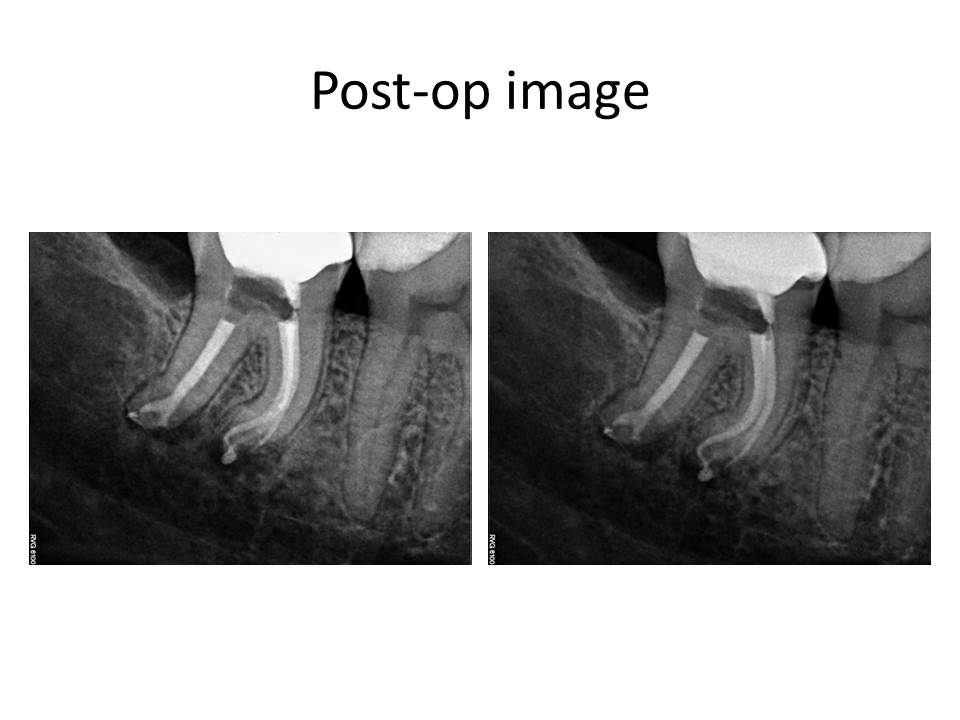

As illustrated by the red outline in the final radiograph, one can see the results of this modification. The canal outline almost appears like a figure eight.

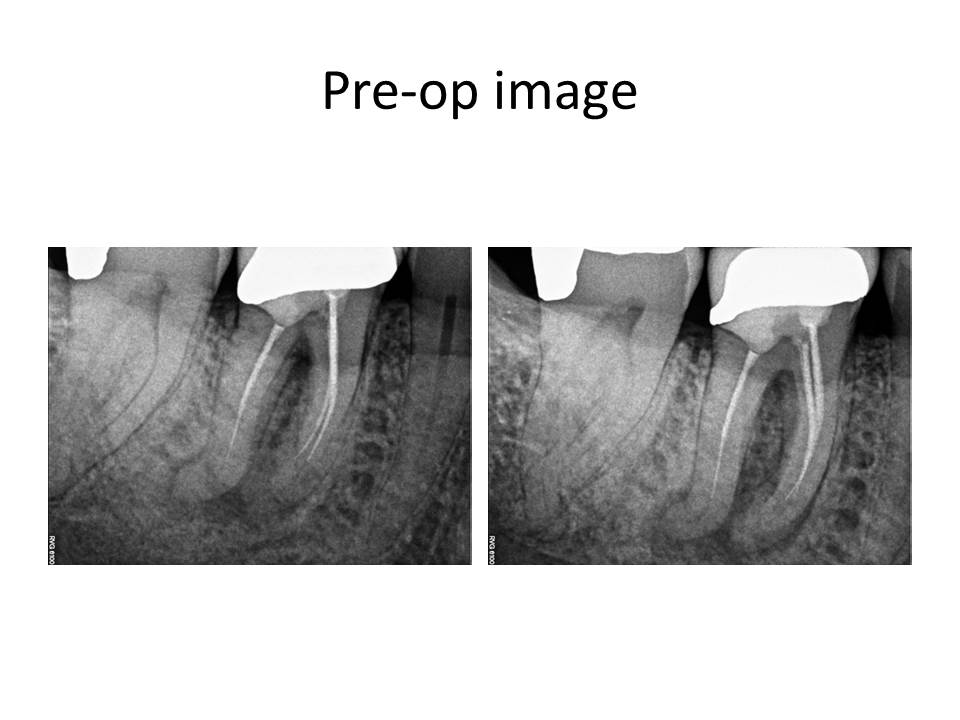

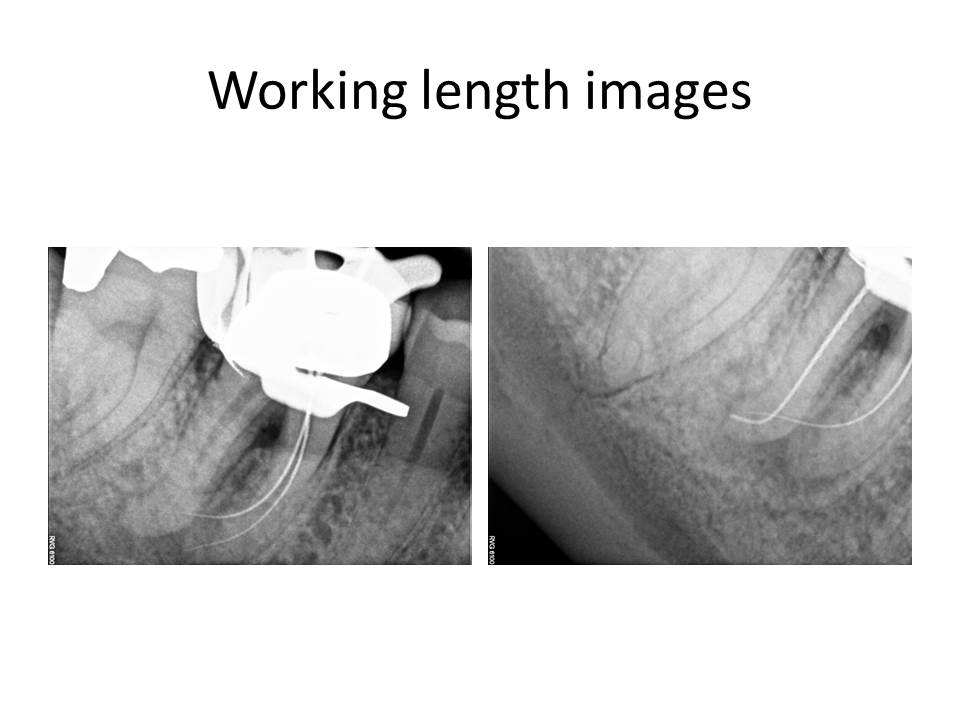

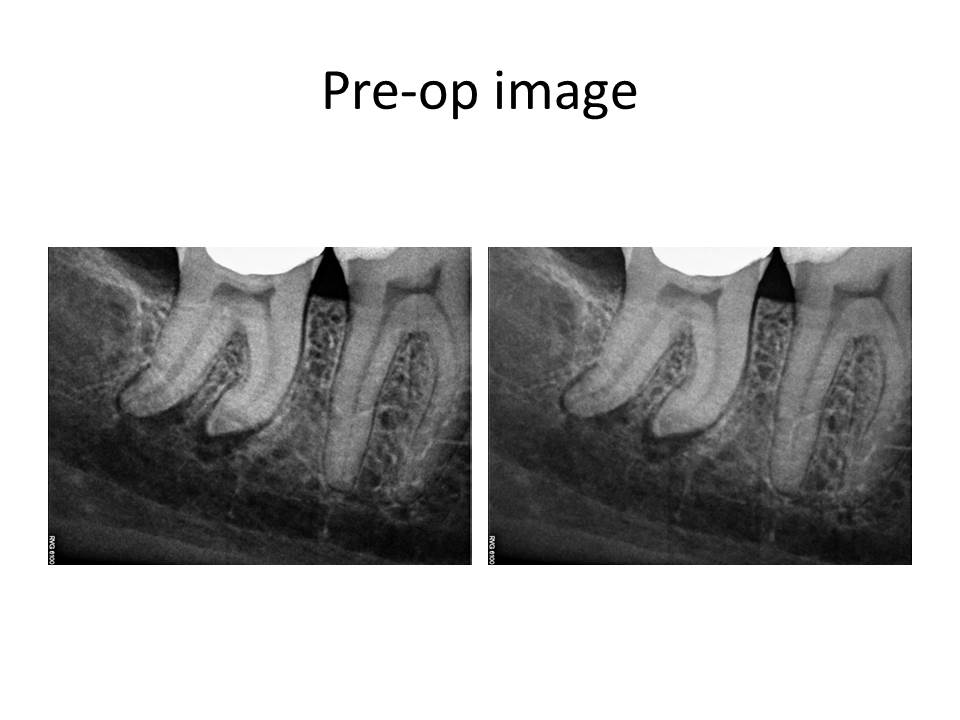

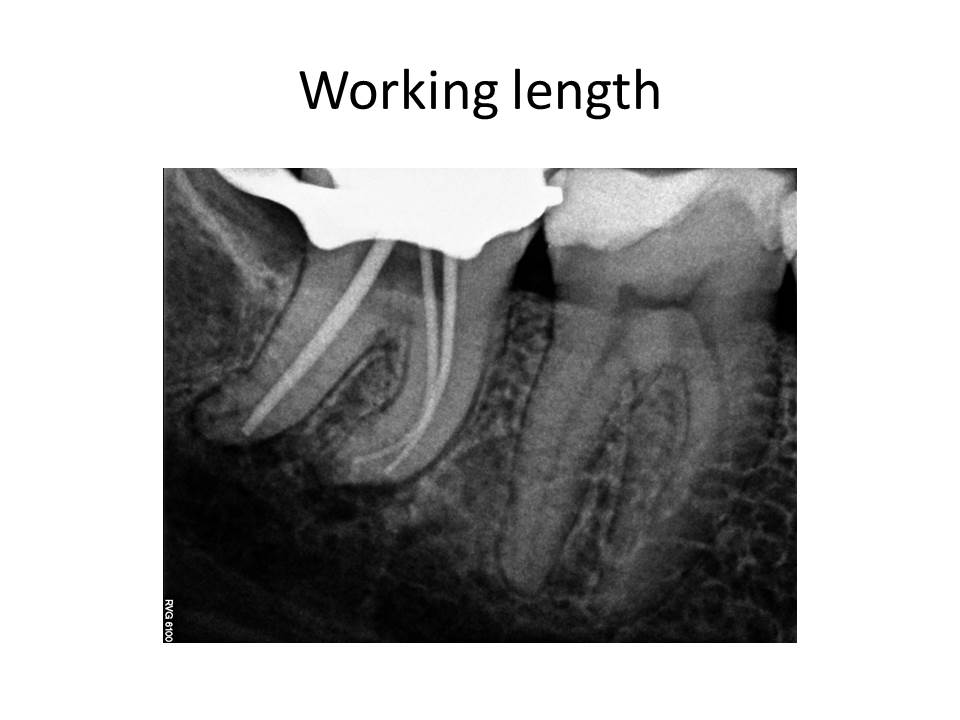

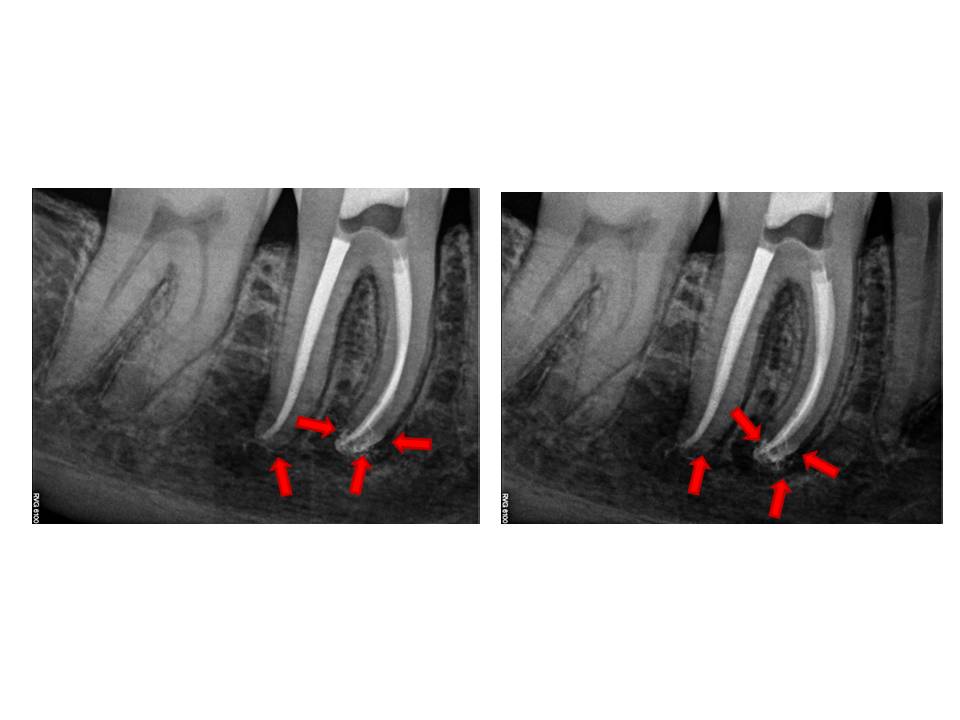

This is an example of a mandibular molar in which the same approach was utilized.

Thank you for supporting my practice. I am open to any questions or thoughts regarding this months post. I strive to elevate my treatments to the highest possible level.

Case of the Month November 2012

1. Preparation design – Step-back, crown-down, double flare, balanced force, modified crown-down, passive step-back, ultrasonic, rotary instrumentation, Self-adjusting file (SAF).

2. Irrigation solutions – sodium hypochlorite in differing concentrations, hydrogen peroxide, saline, local anesthetic, ionized water

3. Chemical means – a chleator either in a cream form applied to the file(RC prep, Prolube, File Eze, Glyde) or an irrigant such as Citric acid, 17% EDTA, Smear Clear, Maleic acid as a final solution prior to obturation.

4. Irrigation solution agitation – Passive ultrasonic, Active ultrasonic (Peizoflow, and there are many others), Tsunami irrigation (Ruddle), Endovac, Continuous Irrigation (SAF).

5: Use of additional irrigants for bacterial removal and canal disinfection – Alcohol, 2% chlorhexidine, Q-mix.

6: Lasers – PIPs

The aformentioned categories are a majority of what has been attempted to produce a canal system in which the residual bacterial load is minimal and there has been a removal of the tissue and debris from lateral canals and canal isthmuses. These, of course, are not all inclusive and there are other steps and solutions that have been attempted.

In my experience, and these are my own thoughts, I think that prevention of a smear layer early on during canal preparation is essential. Playing catch-up after debris has been created and packed into the isthmuses and lateral canals is much more difficult to remove. Since I have modified my irrigation routine, I have noticed that the amount of lateral canals that are evident post-operatively, have appeared more often. I offer these examples as support for this change in canal preparation.

In addition to the modification in irrigation, I still use ultrasonic activation of sodium hypochlorite as a final step. By adjusting the thought process of haow the root canal system is approached, I believe we are able to produce cleaner canals and therefore, increased endodontic success. I am open to any questions or thoughts regarding this months post. Thanks again for supporting my practice. I strive to elevate my treatments to the highest possible level.

Case of the Month November 2011

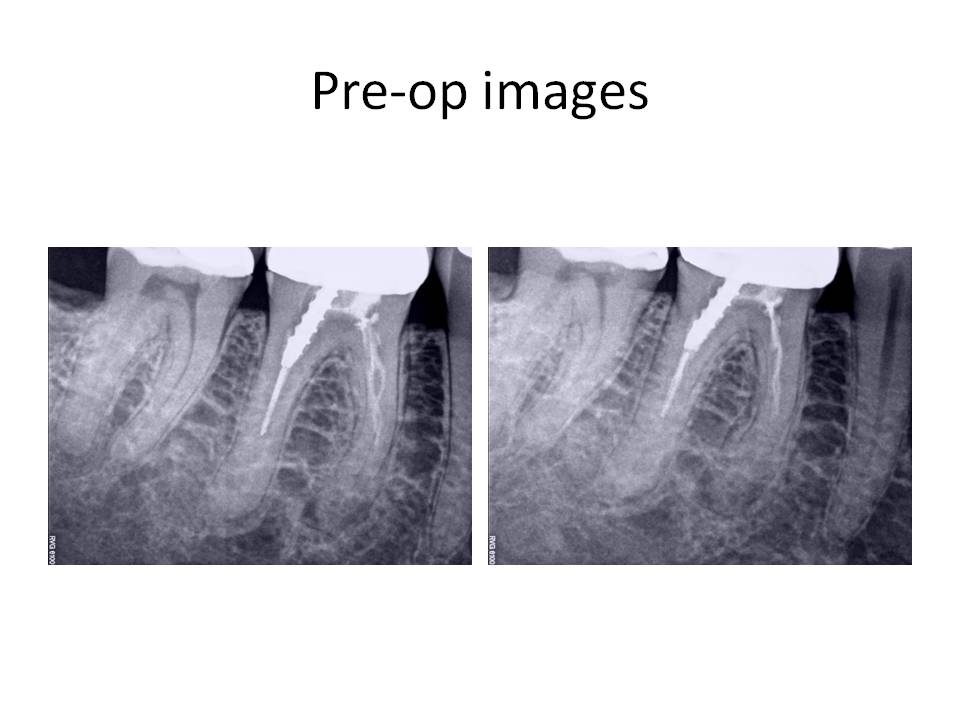

The clinical diagnosis is Previously treated #30 with asymptomatic periapical periodontitis.

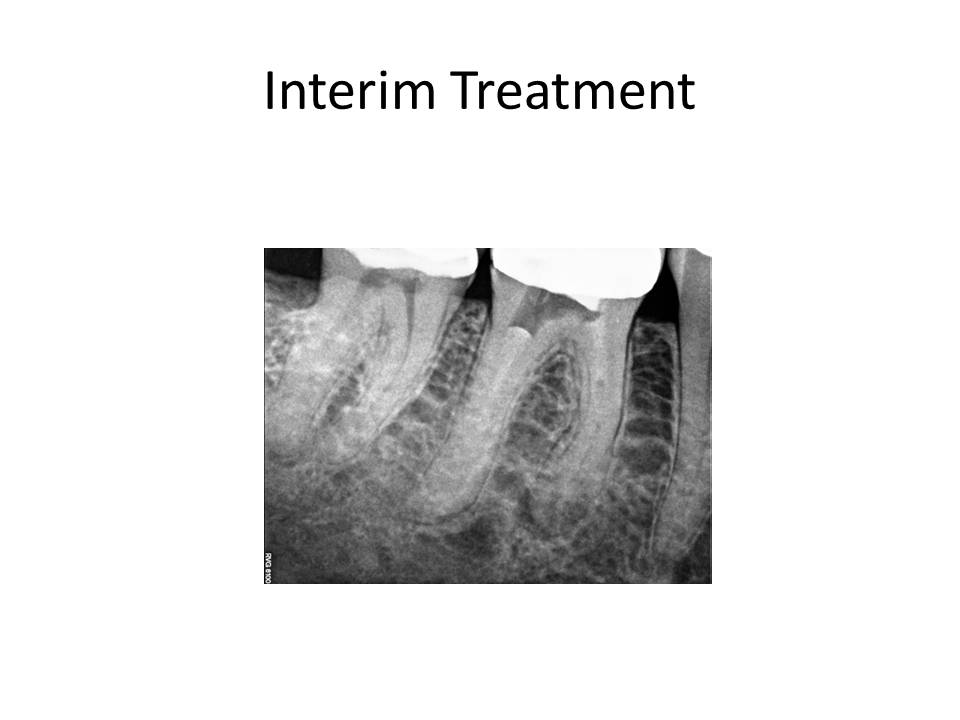

Retreatment of the root canal was recommended and the patient decided to proceed with the treatment. The problems that are anticipated when the case is viewed radiographically are as follows: Preservation of the crn (if possible), removal of the threaded post in the distal root, removal of the carrier-based obturation in the distal root, negotiating the meisal canals after removal of the existing gutta-percha. The mesial canals appear to have been ledged during the previous treatment and this always poses a significant challenge. Careful exploration of the canals with pre-bent small files and a gentle touch is what is needed in these situations. At the initial visit, the tooth was accessed, the threaded post was removed with an ultrasonic and copious water to prevent as much heat transfer to the root as possible. The carrier was removed (Soft-core) from the distal root and this canal was negotiated to the apex. The mesial canals presented with a more difficult challenge to negotiation. The canals were severly ledged and also joined, as evidenced by the drying of one canal led to the other canal being dried as well. I was unable to complete the case in the first appointment. Calcium hydroxide was placed and the patient was reappointed. The interim radiograph is as follows:

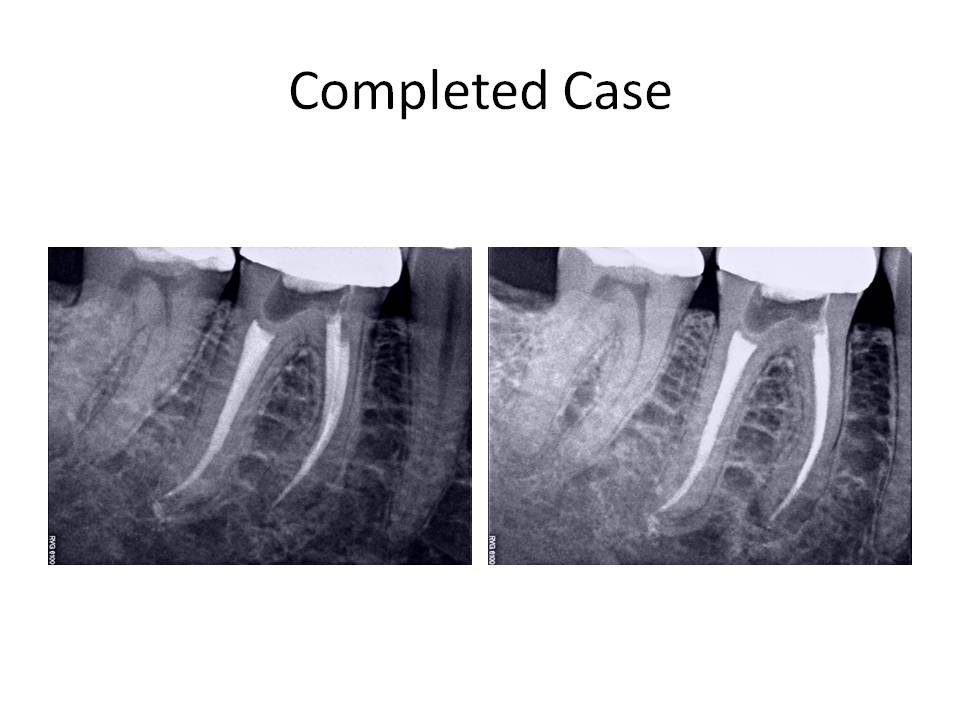

At the second appointment, the patient was asymptomatic, the tooth was again accessed and the process of trying to negotiate the mesial canals was ensued. I think I went through approximately 50 hand files in trying to gain patency. Being persistent paid off and I was finally able to gain access to the apex. The case was cleaned and shaped, and obturated with warm gutta-percha. The completed case is as follows:

This case demonstrated a challenge to canal negotiation. Proper technique and an understanding of my goals was essential in order to properly treat the case. Certainly, I could have initally opted for a root end resection. However, I felt fairly confident that I could manage the retreatment without having to go to an apicoectomy. I welcome any comments or feedback regarding this case. Thank you again for entrusting my office with the care of your valued patients.

Case of the month July 2011

A buccal gingival mini-flap was reflected to permit caries removal. After the caries was excavated, a vital pulp exposure occurred and root canal treatment was initiated. A conservative approach to access was chosen due to the ability to obtain straight line entry into the root canal and opting for conservation of the remaining tooth structure. In doing so, I wanted to maintain the structural integrity and strength of the coronal tooth structure and avoid a crown, if possible. The access preparation is shown as well as the final restoration following root canal treatment.

Final radiographs are as follows:

The patient was recalled in 1 week to evaluate her gingival healing. The tissues appeared to be healing well and within normal limits. She had no complaints of pain.

This case demonstrates that endodontic treatment can be accomplished while conserving as much tooth structure as possible. Traditional access would have dictated an occlusal approach and therefore, the need for a crn. If straight line access can be achieved as well as the remaining goals of endodontic treatment, then a non-traditional approach, such as this case represents, can be accomplished. I welcome any comments or questions. Thank you for supporting our practice. We strive to provide the best treatment for your patients.

Case of the month May 2011

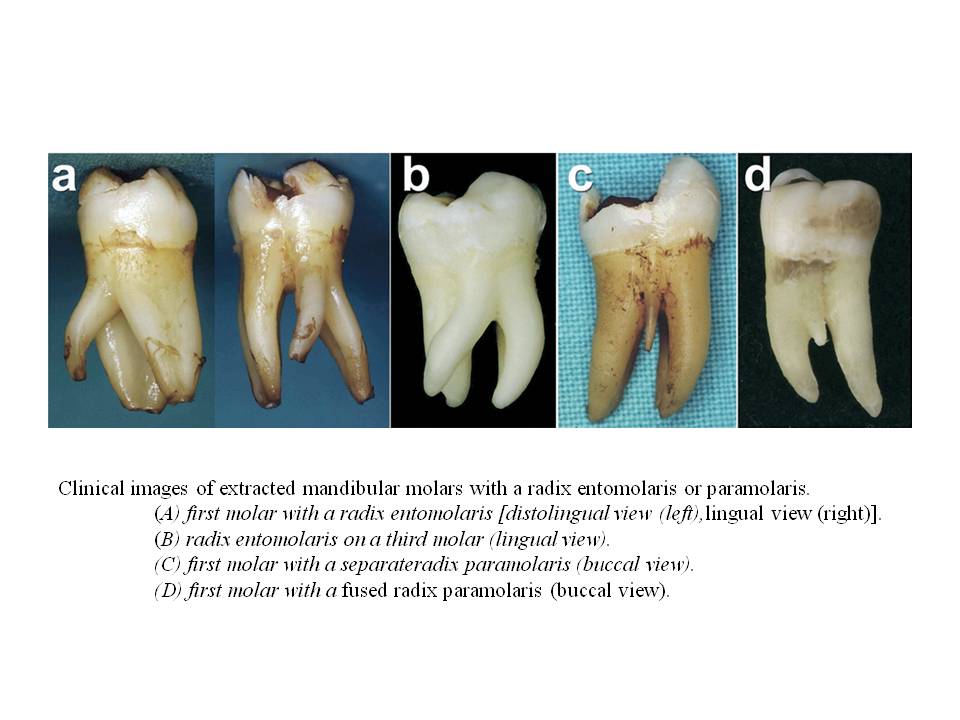

There are two general types of this unusual root anatomy. Radix entomolaris (RE): This supernumerary root is located distolingually in mandibular molars, mainly first molars. Radix paramolaris (RP): An additional root at the mesiobuccal side in mandibular molars. The dimensions of the RE can vary from a short conical extension to a ‘mature’ root with normal length and root canal. In most cases the pulpal extension is radiographically visible. In general, the RE is smaller than the distobuccal and mesial roots and can be separate from, or partially fused with, the other roots. Treatment of these cases involves initial relocation of the orifice to the lingual to achieve straight-line access. However, to avoid perforation or stripping in the coronal third of a severe curved root, care should be taken not to remove an excessive amount of dentin on the lingual side of the cavity and orifice of the RE. The likelihood of instrument separation, root perforation, or canal transportation is elevated in these cases due to the severity of the root curvature. The following images are taken from The Radix Entomolaris and Paramolaris: Clinical Approach in Endodontics Filip L. Calberson, DDS, MMS, Roeland J. De Moor, DDS, MMS, PhD, and Christophe A. Deroose, DDS, MMS. JOE — Volume 33, Number 1, January 2007. These are some extracted molars that demonstrate the variablilty of root anatomy

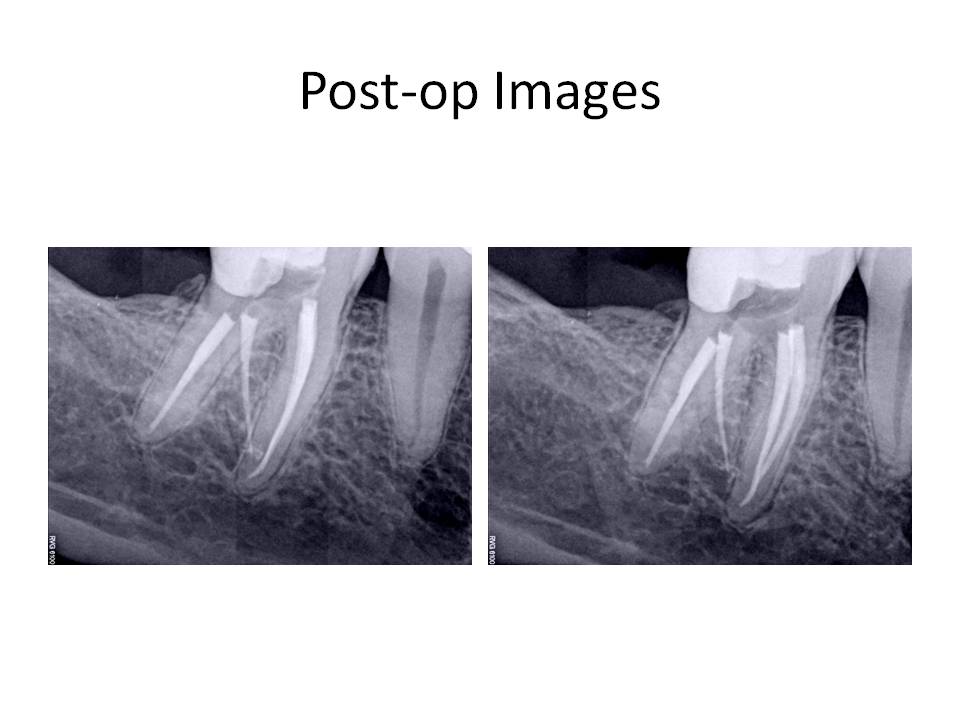

Treatment involved caries removal, GI tem restoration, and RCT. Here are the post-operative images.

I welcome any comments or questions. Thank you for your continued confidence in me and my practice.

Case of the month Feb 2011

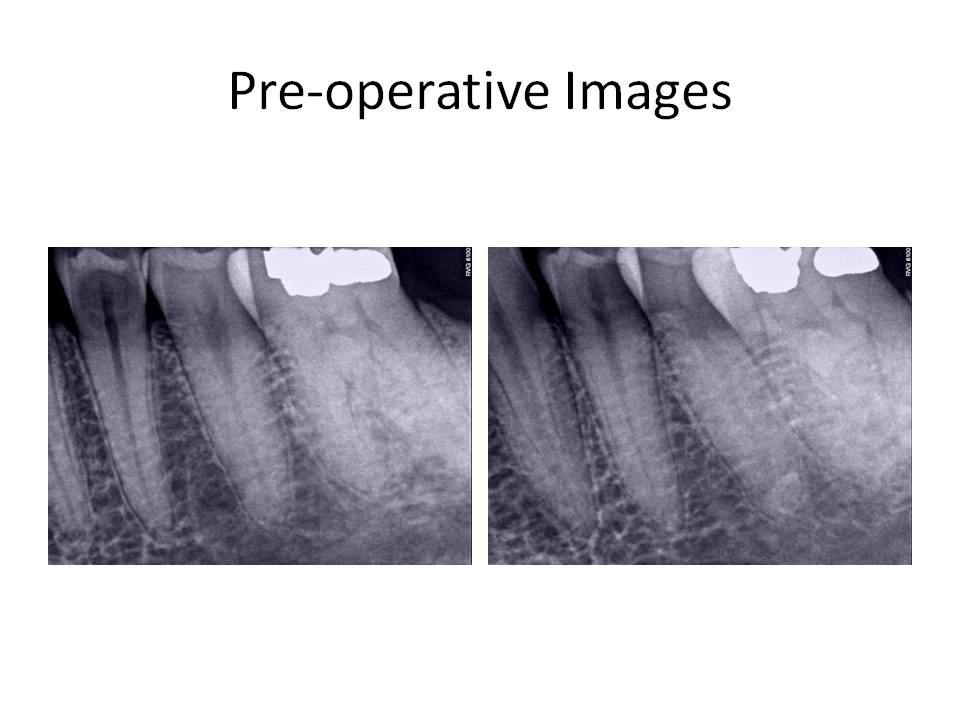

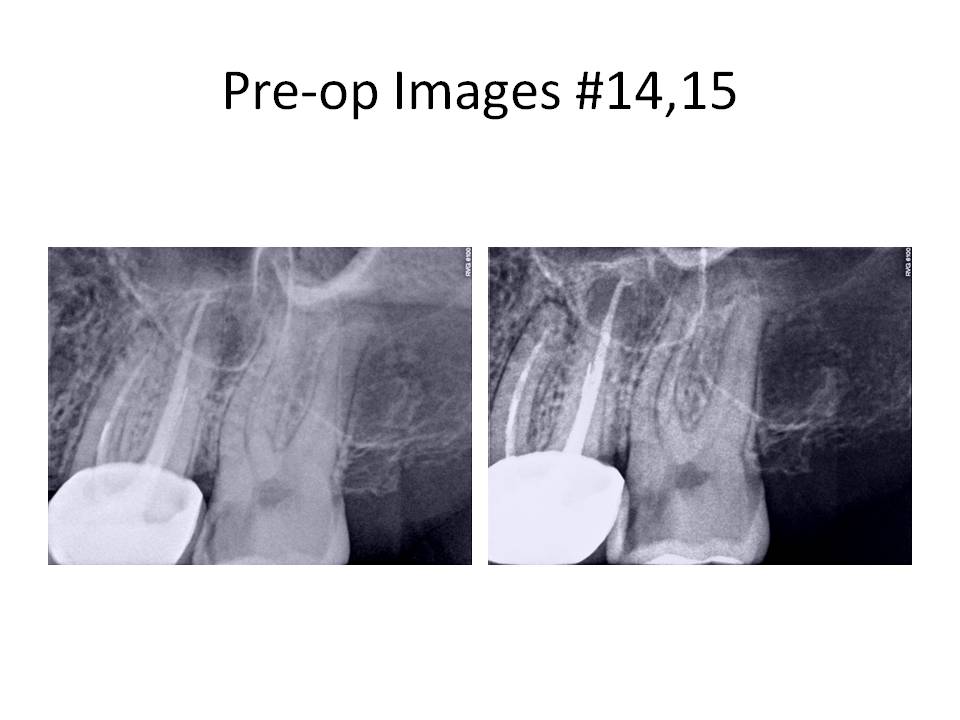

The only positive entry in her medical history was Synthroid for hypothyroid. Clinical Dx #15: Caries #15, Asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis with normal periradicular. Dx #14: Previously treated #14 with asymptomatic periradicular periodontitis.

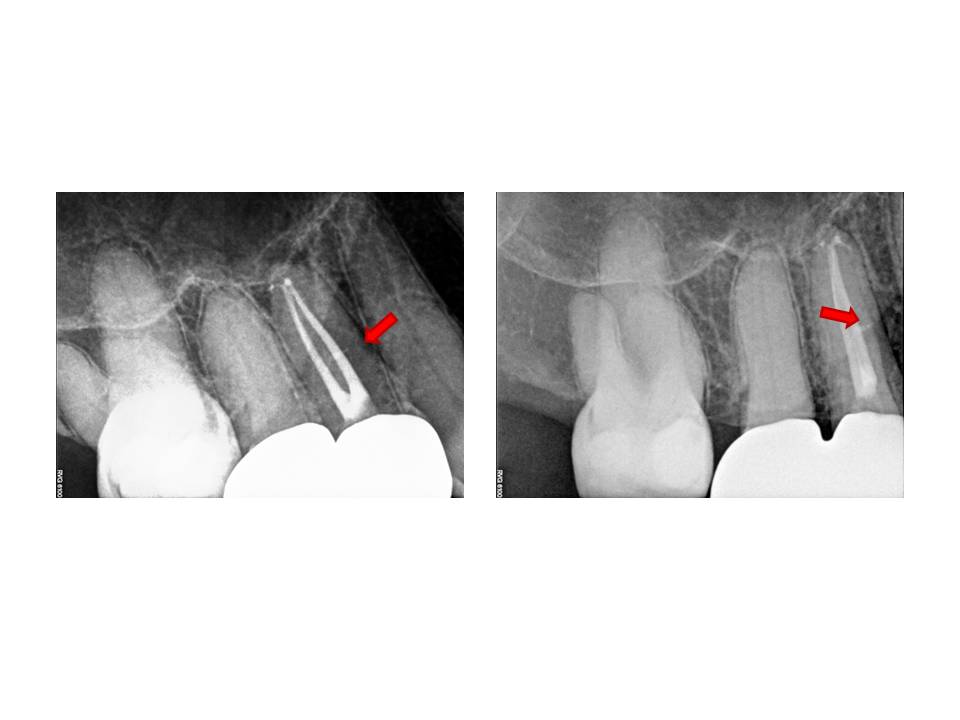

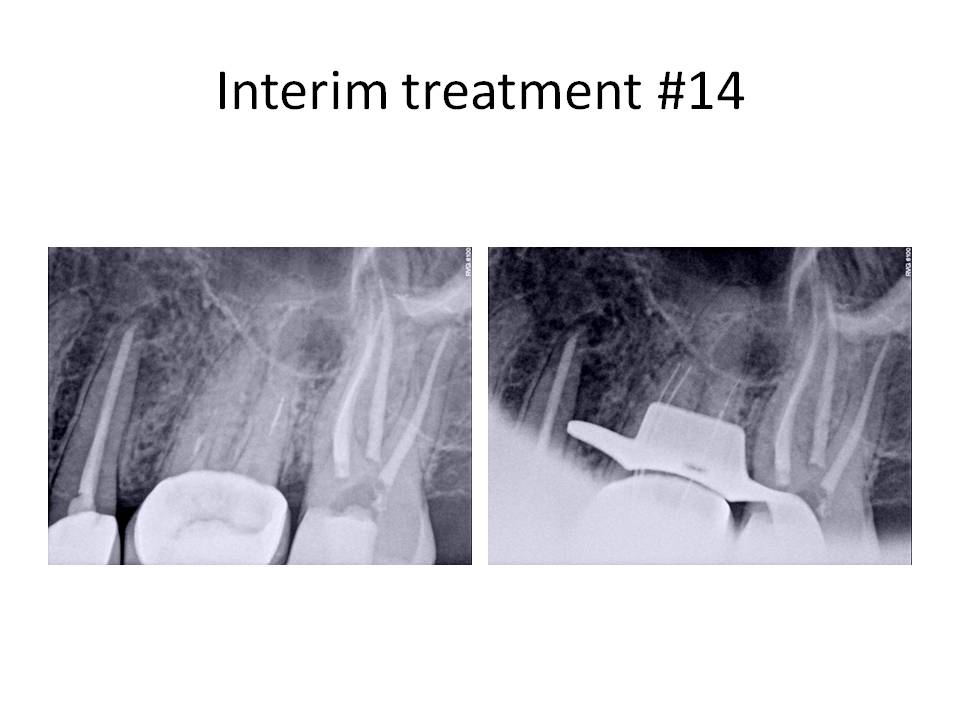

Tooth #15 was treated first. The caries was removed and a vital pulp exposure occurred. The root canal was completed and the patient was appointed for retreatment tooth #14. I will focus on tooth #14 for the remainder of this month’s blog. Tooth was accessed and the Softcore obturation was removed, an untreated MB2 canal was located and instrumented to the apex. An attempt to remove the instrument was not done at this appointment. Calcium hydroxide was placed as an interim medicament and the patient was scheduled to return in 1 week for completion.

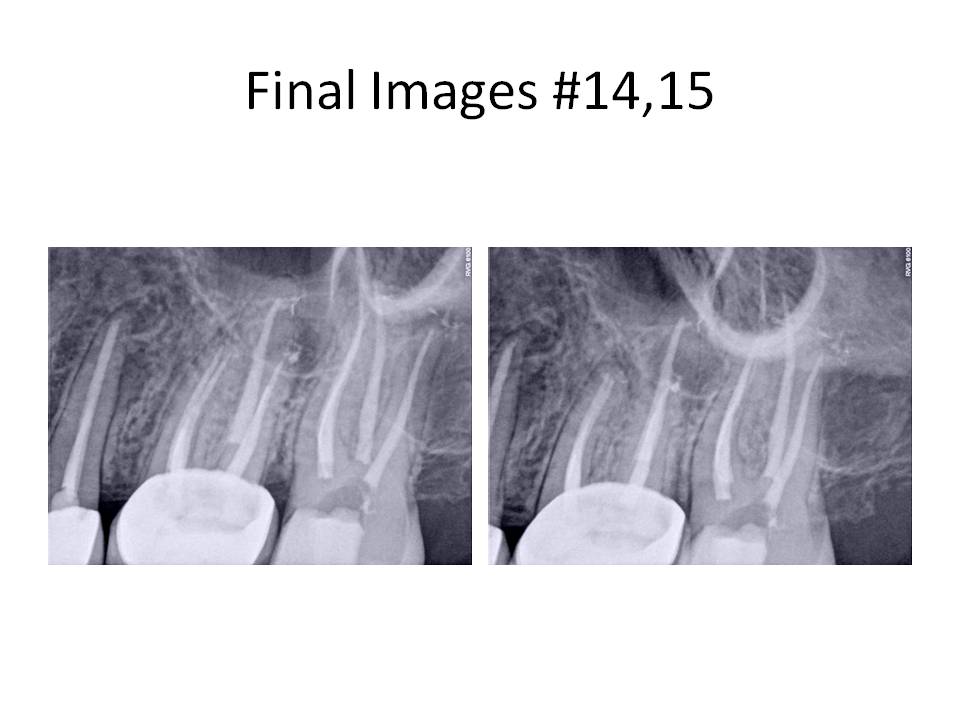

At the next appointment, the file was bypassed to the apex and the root canal was completed.

This case demonstrated that sometimes it is easier to bypass a separated instrument, rather than removing it and sacrificing significant tooth structure during the process. There was a higher potential to bypass the instrument than remove it because it was a hand file. Typically, a rotary file is much more difficult to bypass due to its taper. Final radiographs revealed that tooth #13 had a RL lesion present and previous RCT. The tooth will eventually be retreated. I welcome any questions or comments. Thank you for your continued confidence in my practice, Chris

Case of the Month Jan 2011

The clinical diagnosis was Irreversible pulpitis #31 with symptomatic periradicular periodontitis. The informed consent was signed and administration of local anesthetic was given. After several injections, the patient was still unable to achieve profound anesthesia. I had used 1 carpule of each anesthetic to attempt to adequately numb the area ( 2% Lidocaine with 1:100,000 epi, 3% Mepivicaine, 0.5% Marcaine with 1:200,000 epi, 4% Articaine with 1:100,000 epi). She was given an IAN block, a Gow-Gates, PDL, Buccal Nerve and Lingual Nerve, and an infiltration injection. The endodontic treatment was not attempted, due to lack of profound anesthesia. The patient was dismissed and I recommended that she take 3, 200mg Advil Liquigels 30 minutes prior to her next appointment to help with the anesthesia. There is a paper by Dr. Ken Hargreaves that discusses the use of local anesthetics and how the pH is affected by increasing amounts of epinephrine and why different anesthtic types without epi can be beneficial in these situations. Also, he talks about the need to close the TTX channels with the administration of an NSAID that are typically resistant to local anesthetics.

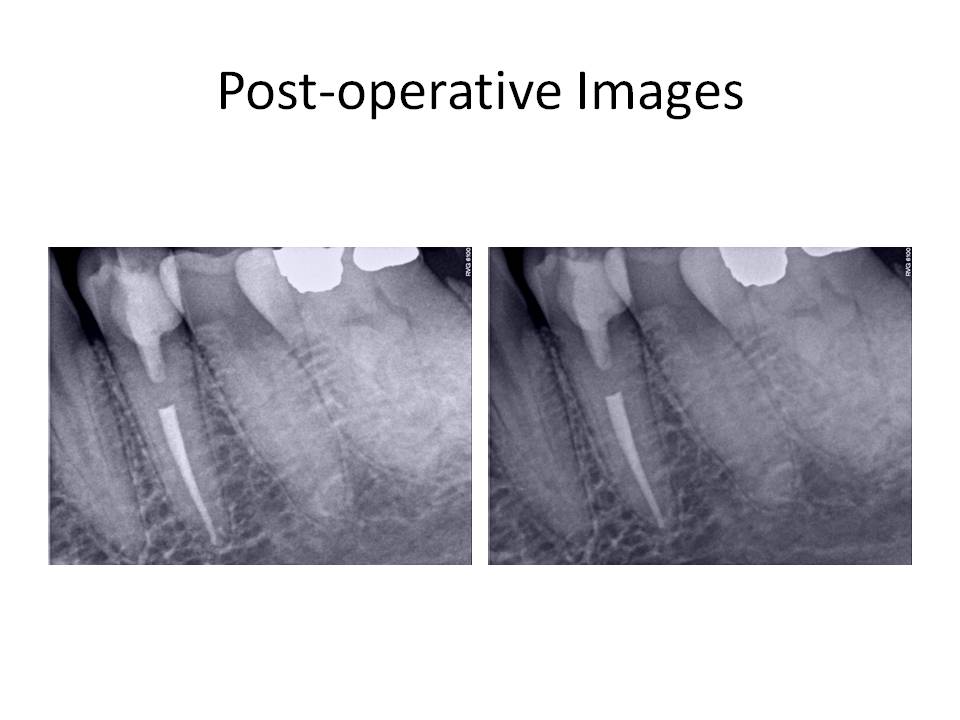

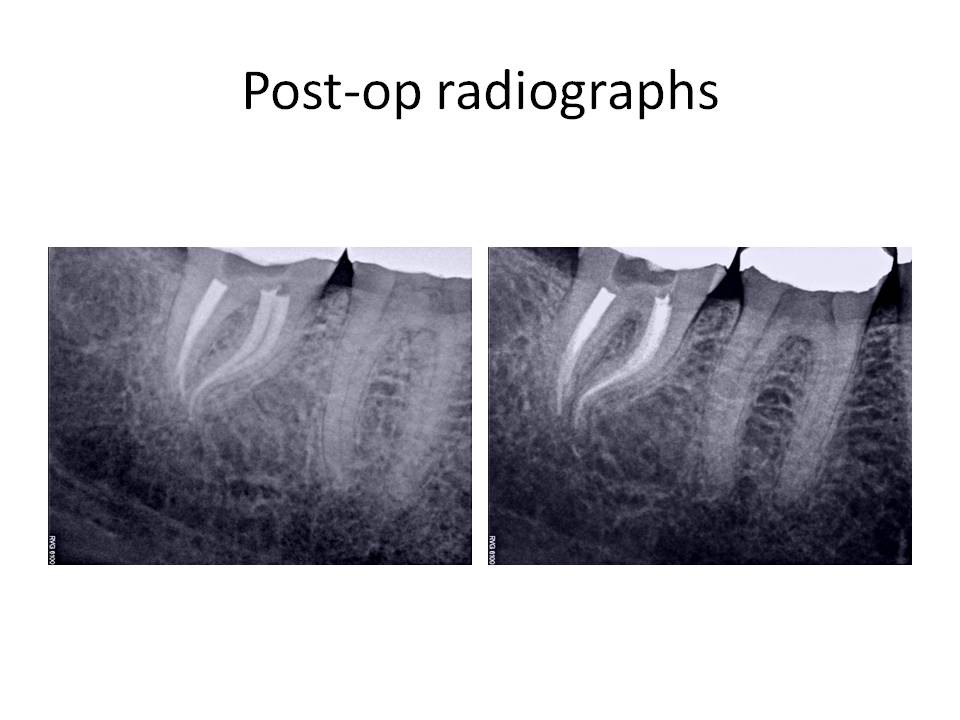

At the next appointment, the same types of anesthetics were given as noted previously, with two exceptions to the first appointment. First, the patient had taken the Advil as directed and second, I gave her a closed mouth injection known as the Akinosi technique of local anesthetic administration. She obtained profound anesthesia and I was able to perform the root canal treatment as planned. Post-op radiographs:

The final radiograph demonstrated two distal canals, one of which (DL), exited very short of the other. I welcome any comments or questions. Thank you for your continued confidence in my practice.